History of Lake Ōkāreka

Lake Ōkareka - this small and little-visited lake is a place of much charm, surrounded by hills nearly everywhere thickly wooded. It is quite near, but out of sight from the tourist motor route of Rotorua and Tarawera; a side road gives access to it. Anglers find good sport there, but otherwise its solitude is not disturbed yet. Many years ago a settler acquired some of the land around it, and built his house on a low-lying isthmus which connects an island-like hill in the middle of the lake with the mainland. Some of the frontage is still in private hands, but the greater part of the sylvan basin in which the lake lies has now become residential property.

Ōkareka means "the lake of sweet food". In early times, Māori grew kūmara or sweet potatoes around the outside of the lake. Lake Ōkareka was first described in print by Sir George Grey, and poetic mention of it is made by Domett in his “Ranolf and Amohia.” Grey visited it on the course of his travels through the Lakes Country to Taupo in the summer of 1849-50. The journey is described in that rare little book entitled “Journal of an expedition Overland from Auckland to Taranaki”, written for the Governor by his secretary G. S. Cooper, with a translation into Maori by his interpreter, Piri-kawau; the book was published in Auckland in 1851. In those days the route from Ōhinemutu to Tarawera was a track which skirted the shore of Ōkareka and reached the large lake near the mission station called Kariri (Galilee). It was a blistering hot day when Governor Grey and his party took the foot trail from Rotorua to Tarawera, and the narrator says they were “nearly stewed”.

“We reached the beautiful lake of Ōkareka,” the journal entry for 27th December 1849, runs, “just at a place where there is a spring of deliciously cool water, wherewith we all refreshed ourselves and then proceeded to cross the lake in canoes. The lake is really an extremely pretty sight, the shores being lofty and wooded, with the exception of a valley at each end, where the roads run. A peninsula, on which stands the pa called Taumaihi, juts out into the centre of the lake. The waters are beautifully clear, and very deep. There is no apparent outlet to this lake. Its vent consists of an underground stream, which is hidden for about half a mile, and then makes its appearance, looking like a fountain, gushing through a heap of rocks and square stones of a basaltic formation, whence it makes its way in a small stream to Tarawera, the level of which is about sixty feet lower than that of Ōkareka, and into which the water falls down a declivity of twenty feet, forming a beautiful cascade, surrounded and overshadowed by a clump of karaka and other evergreen trees.”

In those days the shores of Ōkareka were a scene of Maori life; there were cultivations on the waterside, and the natives fished the waters for whitebait, the koura crayfish, and the little fish called toitoi, which abounded there before the Pakeha trout was introduced. In the ‘sixties Alfred Domett visited Ōkareka and Tarawera by the track Grey took, and we have a picture of the little forest lake in his romantic poem:

Ōkareka means "the lake of sweet food". In early times, Māori grew kūmara or sweet potatoes around the outside of the lake. Lake Ōkareka was first described in print by Sir George Grey, and poetic mention of it is made by Domett in his “Ranolf and Amohia.” Grey visited it on the course of his travels through the Lakes Country to Taupo in the summer of 1849-50. The journey is described in that rare little book entitled “Journal of an expedition Overland from Auckland to Taranaki”, written for the Governor by his secretary G. S. Cooper, with a translation into Maori by his interpreter, Piri-kawau; the book was published in Auckland in 1851. In those days the route from Ōhinemutu to Tarawera was a track which skirted the shore of Ōkareka and reached the large lake near the mission station called Kariri (Galilee). It was a blistering hot day when Governor Grey and his party took the foot trail from Rotorua to Tarawera, and the narrator says they were “nearly stewed”.

“We reached the beautiful lake of Ōkareka,” the journal entry for 27th December 1849, runs, “just at a place where there is a spring of deliciously cool water, wherewith we all refreshed ourselves and then proceeded to cross the lake in canoes. The lake is really an extremely pretty sight, the shores being lofty and wooded, with the exception of a valley at each end, where the roads run. A peninsula, on which stands the pa called Taumaihi, juts out into the centre of the lake. The waters are beautifully clear, and very deep. There is no apparent outlet to this lake. Its vent consists of an underground stream, which is hidden for about half a mile, and then makes its appearance, looking like a fountain, gushing through a heap of rocks and square stones of a basaltic formation, whence it makes its way in a small stream to Tarawera, the level of which is about sixty feet lower than that of Ōkareka, and into which the water falls down a declivity of twenty feet, forming a beautiful cascade, surrounded and overshadowed by a clump of karaka and other evergreen trees.”

In those days the shores of Ōkareka were a scene of Maori life; there were cultivations on the waterside, and the natives fished the waters for whitebait, the koura crayfish, and the little fish called toitoi, which abounded there before the Pakeha trout was introduced. In the ‘sixties Alfred Domett visited Ōkareka and Tarawera by the track Grey took, and we have a picture of the little forest lake in his romantic poem:

Wooded Ōkareka

That mocks you with deceitful mien.

By loving cliffs encompassed round -

Fair captive, so resigned, serene.

Lulled in a seeming sleep profound;

Yet all the while slips off unseen

In secret diving underground.

That mocks you with deceitful mien.

By loving cliffs encompassed round -

Fair captive, so resigned, serene.

Lulled in a seeming sleep profound;

Yet all the while slips off unseen

In secret diving underground.

And he describes its outburst into open day “all flash and foam,” in contrast to the glassy water of the lake. Some of the most beautiful forest in New Zealand is in this reserve, extending to the lofty western side of Lake Ōkataina and the Whakapoungakau Range.

NARRATIVE OF A JOURNEY THROUGH PART OF THE NORTHERN ISLAND OF NEW ZEALAND, IN 1849.

New Zealander 2nd January 1850

New Zealander 2nd January 1850

From Rotorua we took our way to Lake Tarawera, a distance which is easily got over in one day. After walking for some hours through narrow valleys between hills covered with long coarse grass and fern, we came to the shores of a very pretty lake, called Okareka, and embarked in a small canoe, by which we passed up the lake, and shortened the distance considerably. The shores of Lake Okareka are very picturesque, and there is an island in the centre on which a native village is situated and a school house is conspicuous. A short walk from the further end of this small lake brought us in sight of Tarawera, surrounded by high hills, and at the southern side of a lofty mountain whose jagged summit and bare sides have more sternness and grandeur than of beauty in their appearance. We walked along the right bank to the church Mission station, which is at a village on a peninsula projecting into the lake. This nettle-meta has a very pleasing appearance as it is approached: on our arrival we met with a most kind reception from the Resident Missionary, the Rev. Mr. Spencer. The natives who had accompanied us so far, gave such a report of their success in exacting high pay, that when we wanted a canoe to pass up the late next day, the demands made were most exorbitant. Mr. Spencer has been accustomed to live very independently of native assistance, and on this occasion he did not hesitate a moment to take a paddle and jump into a canoe, we followed his example, and with a solitary volunteer, an old chief, sped across the !eke, and soon obtained assistance at another village.

Our object was to reach a very remarkable lake called Rotomahana, or the Hot Lake; by passing from Tarawera through a narrow strait into Areki Lake; and landing at its farther end, a short walk brings the traveller to the shore of the Rotomahana. The scenery is gloomy; but the objects of interest, for which the lake is celebrated, are wonderful and beautiful beyond description. Steam is seen issuing from numerous fissures in the hills, some terrible cauldrons and a geyser are continually heaving, spouting and roaring on the eastern side, but such may be seen in other countries. The real wonders of this lake are two boiling springs, one on either side, which have issued from the hills at a considerable elevation, and formed ponds or lakes of boiling water. The carbonate of lime deposited by the spring has formed a crust round these fairy-like fountains, which gives them the appearance of being enormous basins of the purest marble. The colour which the water assumes in the basins is that of the deepest azure, most charming to gaze upon, amid as it flaws over the edge of the basin's and pours down into the lake, it deposits its mineral substances held in solution in the form of terraces, which look like gigantic flights of marble steps to the fountains above — on one side of the lake they are of various hues, but on the other the deposit is coloured by ferruginous matter, which has given the terrace a pink or roseate appearance. Each step or terrace is about twenty feet broad, and by the falling of the water hallowed out into pools, which look like great shells lined with pearl. These pools form luxurious baths, the temperature varying with the height of the terrace. We plunged into one of them about half way up to the fountain, and could scarcely bear to leave it again, so delightful is it to swim in clear warm water, an a bath which the most gorgeous monarch might envy. We returned to the Mission station before dark, exceedingly pleased with our visit to Rotomahana; and grateful for Mr. Spencer's guidance, without which we would most probably not have seen half its wonders; and like other travellers who were less fortunate, have left it with a far lower idea of the natural curiosities and beauties for which it is so justly celebrated.

A traveller may pass several days pleasantly at Tarawera, making excursions to various pretty spots near—amongst others a waterfall or stream which issues from neighbouring lake and falls into Tarawera. The fall is hidden by fine trees, and the banks of the stream below it are varied and picturesque. The native owner of land near the fall, who acted as our guide, lost my pencil, at which he was greatly afflicted, and seriously offered me possession of the cascade itself as well as the wood immediately about it, as payment for his neglect.

On Sunday Mr. Spencer went to hold service in another village, and left his principal native Teacher to officiate at the station chapel. He conducted the service and preached a short sermon with considerable eloquence, his voice was deep and well-tuned, and the responses of his hearers were made in solemn unison. In the evening I had some conversation with the Teacher and other natives as they sat on the ground near the church about the conduct on his countrymen in holding out for such exorbitant payments, and I expressed our determination to send most of our effects back to the coast and to carry the rest on our own backs rather than submit to such imposition; his wife a fine looking woman, accustomed to European habits from having lived in Mr. Spencer's house, was exceedingly indignant at our being detained after offering a fair payment of 2s per diem to each man and perhaps to her were chiefly indebted for being able to get a party on the following morning. Our first day's journey front Tarawera was a very short one only to Rotokakahi, another lake about six miles off. The Natives live on an island in that lake, and were very civil to us; they had abundance of muscles and a delicious tiny fish called Inanga, of which they gave us a supply. The leading men spent the evening near as talking about the reported murder of a European who lived not far off, they spoke with disgust of the horrid deed and expressed their determination to hold a committee of chiefs for the purpose of considering the best means of bringing the supposed murderers to justice. To us who were entering upon a wild part of the country, beyond the usual visits of the Missionaries, this news was not cheering, more particularly as a young chief came into our hut alone and after closing the door told us in a low voice to be on our guard for his countrymen in the " Taupo" country were not to be trusted, and it would be a source of grief to all right minded natives to hear afterwards that we had been either robbed or murdered. Though we were not inclined to despise his caution yet his fears did not disturb our rest for we felt assured that if any real danger of violence from the Natives was to be apprehended, the good Missionaries whom we had visited would not have failed to warn us of it.

According to our customs we were on our way for is “Taupo" soon after day break. The country we passed over was generally hilly though our path led us through several extensive and fertile valleys, totally destitute of inhabitants; vapour was seen rising from hills and streams, one river which we crossed was quite hot and our natives seemed to delight in every opportunity of enjoying a warm bath.

At sunset we entered an extensive valley bounded on one side by a range of steep hills, burning in many places. The natives chose the immediate vicinity of some boiling mud holes as the best place for encamping; we yielded unwillingly to their anxiety for a warm birth, though the ground on which our tent was pitched seemed to be a mere crust of earth over an incandescent substratum. Before we had finished supper it became so hot that we could not sit upon it and made a hasty retreat to another position. The natives, however, took up our vacated ground, and next morning declared they had passed a pleasant night, sleeping comfortably without shelter, though on terra firma; there was a sharp frost.

Our object was to reach a very remarkable lake called Rotomahana, or the Hot Lake; by passing from Tarawera through a narrow strait into Areki Lake; and landing at its farther end, a short walk brings the traveller to the shore of the Rotomahana. The scenery is gloomy; but the objects of interest, for which the lake is celebrated, are wonderful and beautiful beyond description. Steam is seen issuing from numerous fissures in the hills, some terrible cauldrons and a geyser are continually heaving, spouting and roaring on the eastern side, but such may be seen in other countries. The real wonders of this lake are two boiling springs, one on either side, which have issued from the hills at a considerable elevation, and formed ponds or lakes of boiling water. The carbonate of lime deposited by the spring has formed a crust round these fairy-like fountains, which gives them the appearance of being enormous basins of the purest marble. The colour which the water assumes in the basins is that of the deepest azure, most charming to gaze upon, amid as it flaws over the edge of the basin's and pours down into the lake, it deposits its mineral substances held in solution in the form of terraces, which look like gigantic flights of marble steps to the fountains above — on one side of the lake they are of various hues, but on the other the deposit is coloured by ferruginous matter, which has given the terrace a pink or roseate appearance. Each step or terrace is about twenty feet broad, and by the falling of the water hallowed out into pools, which look like great shells lined with pearl. These pools form luxurious baths, the temperature varying with the height of the terrace. We plunged into one of them about half way up to the fountain, and could scarcely bear to leave it again, so delightful is it to swim in clear warm water, an a bath which the most gorgeous monarch might envy. We returned to the Mission station before dark, exceedingly pleased with our visit to Rotomahana; and grateful for Mr. Spencer's guidance, without which we would most probably not have seen half its wonders; and like other travellers who were less fortunate, have left it with a far lower idea of the natural curiosities and beauties for which it is so justly celebrated.

A traveller may pass several days pleasantly at Tarawera, making excursions to various pretty spots near—amongst others a waterfall or stream which issues from neighbouring lake and falls into Tarawera. The fall is hidden by fine trees, and the banks of the stream below it are varied and picturesque. The native owner of land near the fall, who acted as our guide, lost my pencil, at which he was greatly afflicted, and seriously offered me possession of the cascade itself as well as the wood immediately about it, as payment for his neglect.

On Sunday Mr. Spencer went to hold service in another village, and left his principal native Teacher to officiate at the station chapel. He conducted the service and preached a short sermon with considerable eloquence, his voice was deep and well-tuned, and the responses of his hearers were made in solemn unison. In the evening I had some conversation with the Teacher and other natives as they sat on the ground near the church about the conduct on his countrymen in holding out for such exorbitant payments, and I expressed our determination to send most of our effects back to the coast and to carry the rest on our own backs rather than submit to such imposition; his wife a fine looking woman, accustomed to European habits from having lived in Mr. Spencer's house, was exceedingly indignant at our being detained after offering a fair payment of 2s per diem to each man and perhaps to her were chiefly indebted for being able to get a party on the following morning. Our first day's journey front Tarawera was a very short one only to Rotokakahi, another lake about six miles off. The Natives live on an island in that lake, and were very civil to us; they had abundance of muscles and a delicious tiny fish called Inanga, of which they gave us a supply. The leading men spent the evening near as talking about the reported murder of a European who lived not far off, they spoke with disgust of the horrid deed and expressed their determination to hold a committee of chiefs for the purpose of considering the best means of bringing the supposed murderers to justice. To us who were entering upon a wild part of the country, beyond the usual visits of the Missionaries, this news was not cheering, more particularly as a young chief came into our hut alone and after closing the door told us in a low voice to be on our guard for his countrymen in the " Taupo" country were not to be trusted, and it would be a source of grief to all right minded natives to hear afterwards that we had been either robbed or murdered. Though we were not inclined to despise his caution yet his fears did not disturb our rest for we felt assured that if any real danger of violence from the Natives was to be apprehended, the good Missionaries whom we had visited would not have failed to warn us of it.

According to our customs we were on our way for is “Taupo" soon after day break. The country we passed over was generally hilly though our path led us through several extensive and fertile valleys, totally destitute of inhabitants; vapour was seen rising from hills and streams, one river which we crossed was quite hot and our natives seemed to delight in every opportunity of enjoying a warm bath.

At sunset we entered an extensive valley bounded on one side by a range of steep hills, burning in many places. The natives chose the immediate vicinity of some boiling mud holes as the best place for encamping; we yielded unwillingly to their anxiety for a warm birth, though the ground on which our tent was pitched seemed to be a mere crust of earth over an incandescent substratum. Before we had finished supper it became so hot that we could not sit upon it and made a hasty retreat to another position. The natives, however, took up our vacated ground, and next morning declared they had passed a pleasant night, sleeping comfortably without shelter, though on terra firma; there was a sharp frost.

Journey from Taranaki to Rangitikei - Taranaki News 1858

The account describes a journey from Taranaki to Mokau, Taupo, Rotomahana, Tarawera and Rangitikei. On the 4th January 1858 our party, consisting of F. Murray, J. McKellar, A. Standish, W. Hursthouse, and myself (P. Smith), started on their long talked of journey to Lake Taupo, which they had discussed last year on the top of Mt. Egmont.

https://tiaki.natlib.govt.nz/#details=ecatalogue.22766

https://tiaki.natlib.govt.nz/#details=ecatalogue.22766

Monday, 25th January. — Started at five without any breakfast. In about an hour we got a view of Lake Tarawera through the hills, and at seven we came to a hill overlooking Rotomahana, from which clouds of steam were rising from the in-numerable hot springs that surround this lake.

We were rather disappointed in the lake as to prettiness, it being encompassed by high hills, with dead-looking fern growing upon them, and in some places a little manuka on the edge of the lake; nevertheless the view from this hill is very grand; in the distance, towards the north, are the Horohoro mountains, with their table-like tops and steep sides; under them is a peep of Tarawera lake, and again in the line, at the northern end of Rotomahana, is the beautiful and celebrated Tarata cascade.

On the left or western side was the Wakatarata, another warm cascade, resembling the Tarata in appearance, but with the colors more varied. In the middle of the lake are the pretty Chinese-looking islands of Puwai and Pukara, covered with houses and manuka. The lake must be a very Paradise for ducks, which breed in immense numbers in its tepid waters, covering it in some places like a black cloud; whilst numerous toreas and pukekos are to be seen bathing in the warm water, or feeding amongst the rushes.

We were rather disappointed in the lake as to prettiness, it being encompassed by high hills, with dead-looking fern growing upon them, and in some places a little manuka on the edge of the lake; nevertheless the view from this hill is very grand; in the distance, towards the north, are the Horohoro mountains, with their table-like tops and steep sides; under them is a peep of Tarawera lake, and again in the line, at the northern end of Rotomahana, is the beautiful and celebrated Tarata cascade.

On the left or western side was the Wakatarata, another warm cascade, resembling the Tarata in appearance, but with the colors more varied. In the middle of the lake are the pretty Chinese-looking islands of Puwai and Pukara, covered with houses and manuka. The lake must be a very Paradise for ducks, which breed in immense numbers in its tepid waters, covering it in some places like a black cloud; whilst numerous toreas and pukekos are to be seen bathing in the warm water, or feeding amongst the rushes.

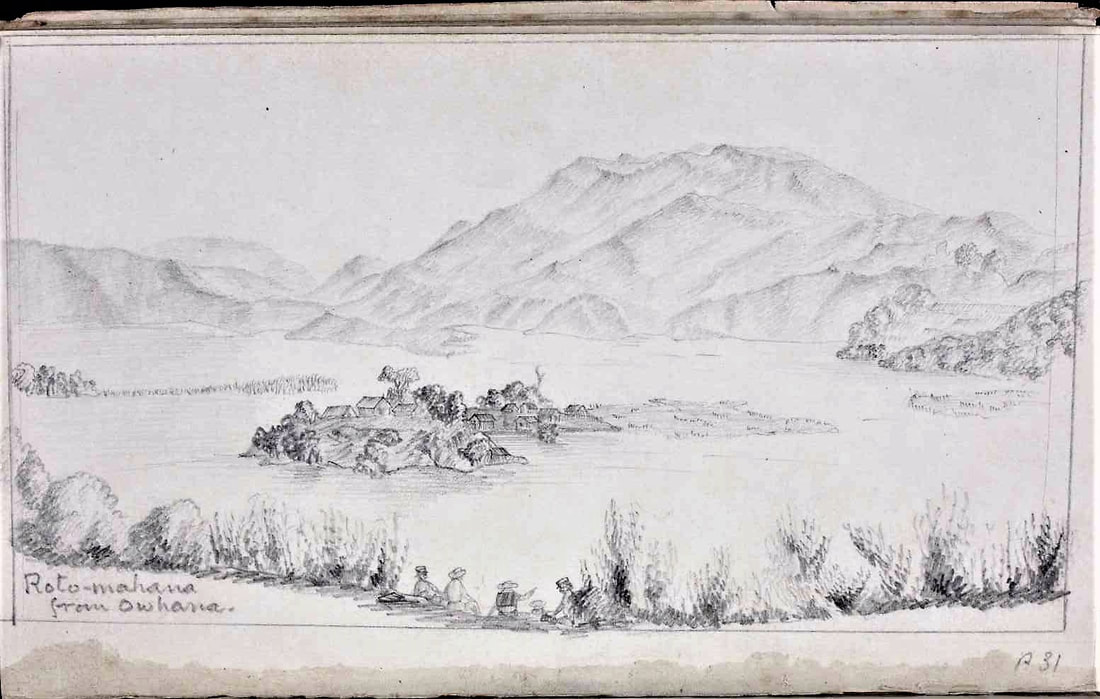

January 1858: Lake Rotomahana from Ohana

Having rested some time, we descended and crossed a warm stream and swamp, through some manuka scrub, and passed many boiling springs. On account of the latter, it is very dangerous to step-out of the path, for you stand a good chance of getting boiled to a jelly before any assistance could be rendered you. In many places the crust of earth over the boiling cauldrons below is so thin that it shakes as you walk across it. Everything about has a boiled look, with the exception of the manuka trees, which seem to flourish well. After crossing a delightfully warm stream running from one part of the lake to another, we put on our boots and scrambled through some scrub to a few houses, used by the Maories when they come here to catch ducks.

The houses about Rotomahana seem to be all very cosey little places, often built over a hot spring, which always keeps them warm. Scattered amongst the houses are an immense number of large square slabs of white stone, laid in a horizontal position over hot springs, and are used by the natives for drying tawa berries; this, I believe, being the only place in New Zealand where they can be done. All the birds about the lake are strictly tapu at this season, therefore we were unable to shoot any.

Leaving this settlement (called Ohana), we passed a deep, clear, boiling cauldron, into which, some years ago, fell two girls; the elder went to get a kite of potatoes out of the hole, having a child on her back; as she stooped, the little one slipped over her head into the boiling water, and the girl, in trying to get her out, fell in also. After passing this human saucepan, we came to another deserted settlement called Takapu; and stopped to have some breakfast, which we spread out on some of the hot slabs, but found them uncomfortably warm, so had to shift our quarters. We made our chocolate from the boiling water of the springs; at first we liked it, but soon changed our opinions, as it had a most sickly disagreeable taste.

After leaving Takapu, we passed through some manuka scrub, in the centre of which is a large boiling pond about 40 feet in diameter; the water in the middle was springing furiously up, sometimes to the height of ten feet, and at others only three. It was surrounded by rocks and manuka, and appeared to be very deep. It is called Hahapu. The water from it ran by a channel cut in the rock into some baths, which were well pared and sided with large flat stones. After passing this, we turned a corner, and the beautified Tanta burst upon our view. We seemed all at once to have entered fairy land, we walked upon what appeared to be white marble, before us were dozens of marble baths and terraces, with the elegant little toreas hopping about, and bathing in the warm water that falls from terraces, getting gradually cooler as it nears the lake. The toreas seem to lead a happy life, free from the cares of their wilder brethren of Taupe, who are likely at any moment to fall a prey to the ruthless stick or stone of any Maori boy who passes along; these lucky rascals, protected by the tapu, have nothing to do but hop up and down all day long, first on one leg then on the other, warming their feet in the water, and then jump into the air with a loud scream.

Our guides upon reaching the baths immediately immersed themselves in them, and seemed to enjoy it exceedingly; probably they had not been washed since last time they were here — about six months previous. Whilst they were performing their ablutions, we ascended the terraces to the large basin on the top, the water of which is too hot to hold one's hand in; it is a most beautiful blue, as is also the steam rising from it. The basin is about 40 feet across, and go above the level of the lake, towards which it descends in terraces, which spread out and increase in number near the bottom. The terraces vary in height from six feet to six inches, a great many of them being above the latter height. I think the best idea that can be given of the Tarata is to imagine an immense surf 60 feet high just after it has broken, and is all foam. The Tarata is, I believe, composed of siliceous deposit.

We now left Rotomahana, passing, on our road to Tarawera, the Ariki, a hill where the Maories were fighting some time ago, and kept along the eastern side of the Kaiwaka stream, which joins the two lakes; half a mile from Rotomahana it is joined by the Araporohe, which carries of the waters of Rotomakariri, small lake to the eastward. About a mile from the Tarata we reached a branch of Lake Tarawera, at the mouth of the Kaiwaka river. On the top of a bill is a pa called Pukekuore; we did not go to it, but kept along the lake to Koutu, where our guides got a canoe. From here we paddled along the eastern side of the arm of the lake till opposite Moura point, when we turned to the north-west.

Tarawera far surpasses Taupo and Rotomahana in beauty. The arm we came along is about two miles long, and nearly as broad in some places; the eastern bank is steep and covered with Pohutakawa trees, then in full bloom, which added considerably to the beauty of the scenery; in some places bold rocky cliffs stand out into the lake, with beautiful little bays on each side, and trees growing in the ravines, dipping their branches into the water. In many places we paddled along under the branches of the Pohutakawa trees, disturbing the ducks as we went along. A. S. shot two of them. After passing Moura (a pretty pa built at the southern side of the arm on the top of some beautiful white cliffs), we got into the body of the lake, and at one arrived at Kauehape, the home of our guides, where we partook of some potatoes, dried trey fish, and tutu wine.

The houses about Rotomahana seem to be all very cosey little places, often built over a hot spring, which always keeps them warm. Scattered amongst the houses are an immense number of large square slabs of white stone, laid in a horizontal position over hot springs, and are used by the natives for drying tawa berries; this, I believe, being the only place in New Zealand where they can be done. All the birds about the lake are strictly tapu at this season, therefore we were unable to shoot any.

Leaving this settlement (called Ohana), we passed a deep, clear, boiling cauldron, into which, some years ago, fell two girls; the elder went to get a kite of potatoes out of the hole, having a child on her back; as she stooped, the little one slipped over her head into the boiling water, and the girl, in trying to get her out, fell in also. After passing this human saucepan, we came to another deserted settlement called Takapu; and stopped to have some breakfast, which we spread out on some of the hot slabs, but found them uncomfortably warm, so had to shift our quarters. We made our chocolate from the boiling water of the springs; at first we liked it, but soon changed our opinions, as it had a most sickly disagreeable taste.

After leaving Takapu, we passed through some manuka scrub, in the centre of which is a large boiling pond about 40 feet in diameter; the water in the middle was springing furiously up, sometimes to the height of ten feet, and at others only three. It was surrounded by rocks and manuka, and appeared to be very deep. It is called Hahapu. The water from it ran by a channel cut in the rock into some baths, which were well pared and sided with large flat stones. After passing this, we turned a corner, and the beautified Tanta burst upon our view. We seemed all at once to have entered fairy land, we walked upon what appeared to be white marble, before us were dozens of marble baths and terraces, with the elegant little toreas hopping about, and bathing in the warm water that falls from terraces, getting gradually cooler as it nears the lake. The toreas seem to lead a happy life, free from the cares of their wilder brethren of Taupe, who are likely at any moment to fall a prey to the ruthless stick or stone of any Maori boy who passes along; these lucky rascals, protected by the tapu, have nothing to do but hop up and down all day long, first on one leg then on the other, warming their feet in the water, and then jump into the air with a loud scream.

Our guides upon reaching the baths immediately immersed themselves in them, and seemed to enjoy it exceedingly; probably they had not been washed since last time they were here — about six months previous. Whilst they were performing their ablutions, we ascended the terraces to the large basin on the top, the water of which is too hot to hold one's hand in; it is a most beautiful blue, as is also the steam rising from it. The basin is about 40 feet across, and go above the level of the lake, towards which it descends in terraces, which spread out and increase in number near the bottom. The terraces vary in height from six feet to six inches, a great many of them being above the latter height. I think the best idea that can be given of the Tarata is to imagine an immense surf 60 feet high just after it has broken, and is all foam. The Tarata is, I believe, composed of siliceous deposit.

We now left Rotomahana, passing, on our road to Tarawera, the Ariki, a hill where the Maories were fighting some time ago, and kept along the eastern side of the Kaiwaka stream, which joins the two lakes; half a mile from Rotomahana it is joined by the Araporohe, which carries of the waters of Rotomakariri, small lake to the eastward. About a mile from the Tarata we reached a branch of Lake Tarawera, at the mouth of the Kaiwaka river. On the top of a bill is a pa called Pukekuore; we did not go to it, but kept along the lake to Koutu, where our guides got a canoe. From here we paddled along the eastern side of the arm of the lake till opposite Moura point, when we turned to the north-west.

Tarawera far surpasses Taupo and Rotomahana in beauty. The arm we came along is about two miles long, and nearly as broad in some places; the eastern bank is steep and covered with Pohutakawa trees, then in full bloom, which added considerably to the beauty of the scenery; in some places bold rocky cliffs stand out into the lake, with beautiful little bays on each side, and trees growing in the ravines, dipping their branches into the water. In many places we paddled along under the branches of the Pohutakawa trees, disturbing the ducks as we went along. A. S. shot two of them. After passing Moura (a pretty pa built at the southern side of the arm on the top of some beautiful white cliffs), we got into the body of the lake, and at one arrived at Kauehape, the home of our guides, where we partook of some potatoes, dried trey fish, and tutu wine.

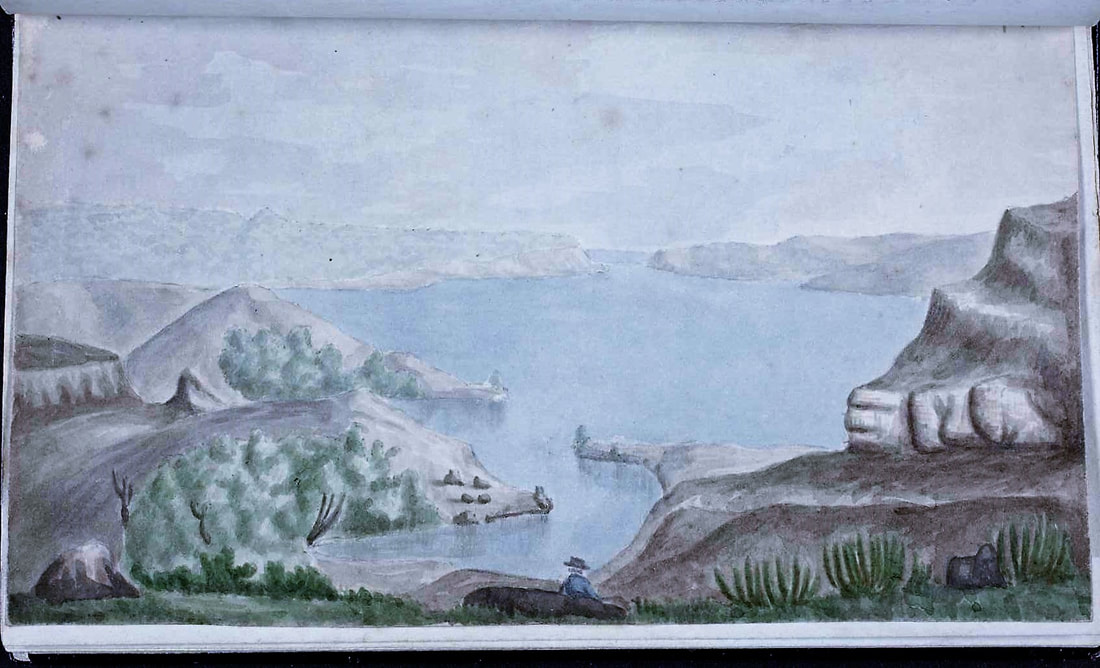

January 1858: Lake Tarawera from Te Mu

At two we started again in another canoe for Te Mu, the residence of Mr. Spencer, situated at the western end of Tarawera, about five miles from Kauehape. We passed up a pretty little arm of the lake to a settlement called Poniromia, where we landed our things. Our guides now demanded 6 shillings, instead of the 4 shillings we had promised them to bring us from Rotomahana, which we refused to give; but, whilst we were not looking, they seized upon F. M.'s pack, and jumped into their canoe and made off, telling us they would not give it up till we had paid the 6 shillings. We told them we should not pay them, and that they might take the pack at their peril. A man now came down from the pa, and called out to them to bring back the pack, which, after some time, they did.

We then ascended a rocky path, and on the top, to our great surprise, came upon a broad cart-road, with trenches cut on each side, &c.; but we were more surprised, a little further on, when, upon turning a corner, we beheld a regular village laid out in European style, instead of being huddled up together in a heap, as most Maories live. We were met by a number of Maories, who shook hands all round, and guided us to the chief's house, which seems to be used by travellers. The chief's name is Kemp, and he seemed to be a nice, straight-forward, honest man, dressed entirely in English costume.

There was an Englishman named H. Sampson located here to impart instruction to the natives. J. M. had a letter to Mr. Spencer, which he went to deliver: and was kindly invited to stop at the mission house till we left Tarawera, which we expected to do in a day or two. The Maories have a mill here, and we bought from them 40 lbs. of flour at 2 dollars per pound. The Wairoa river (from which the village takes its name) runs just behind the house.

Tuesday, 26th. — Mr. Spencer and J. M. came down to ask us to go to Rotokakahi, which is about a mile from the mission house. We kept along the road past the mill; which is a very nice, strongly-built little place; the stone-work was done by the Maories, and speaks volumes for their mechanical skill; and passed over a little trellis-worked bridge thrown across the Wairoa river; it was made entirely by the Maories as a surprise for Mr. Spencer when he returned from a journey once; it is about 20 feet long and 5 broad, and is painted green.

We now earns in sight of Rotokakahi (lake of shell-fish; there is not one to be found in it), upon the banks of which we procured two canoes, and raced for three miles as far as Motutawa, an island situated at the western end of the lake. On it is built a pa with a great many carvings about it. Having visited the church, which is built of grass, and looks very neat and comfortable, we again started, pulled across to a pa on the southern side called Kaitiriria (all its inhabitants Catholics), and then round by the north side of the lake to the eastern end, where we got out, walked over a hill about a furlong in length, and were rewarded for our pains by a sight of the beautiful lake Tikitapu.

It is about a mile long by the same in width; in some places the trees grow down to the edge of it, and in others it is fern and manuka; altogether, it is a beautiful little lake. The water is a very deep indigo colour, and very clear; far different from Rotokakahi, the water of which is quite yellow, and full of small particles of pollen from the fern grown, on its banks. After admiring the lake for some time, we returned to the canoes, pulled hack across the lake again, and left the canoes where we found them in the morning. We then returned to the village, and were invited to dine with Mr. Spencer. He has a beautiful house and garden here, and in the latter we observed some elms and oak quite 20 feet high. The oak was covered with acorns.

Wednesday, 27th. — One of our party was now laid up with a bad leg, so as we should not be able to get to Pukawa in the eight days, the two Maories whom we left there would be off home. Mr. S., J. M., A. S., and myself therefore started for Rotorua lake. Passing Rotokakahi, Tikitapu, and a piece of bush, we entered some fine grassy valleys, along which we continued until we came to two paths; Mr. S. took the one leading to Te Ngae, the, old mission, whilst we proceeded along one that led south-west for about a mile, then sharp to the north, over some small hills, from the top of which we beheld Rotorua, the largest lake except Taupo in New Zealand. I believe it is about 12 miles long by 8 broad. It has the large island of Mokoia near the middle, which was once the stronghold of all the Maories about here, and was considered impregnable till the great Hongi, having hauled canoes overland from the Bay of Plenty, took it and massacred most of its inhabitants. It is now a celebrated place for kuineras.

We descended, and, walking cautiously among the hot springs, arrived at a settlement called Wakarewarewa, and partook of some potatoes cooked in one of the boiling springs, without any disagreeable taste, as we expected them to have. The springs about here are not near so fine as those of Rotomahana, though I believe some-times there are some splendid jets of water shooting up to the height of 30 feet; they were not at work during our visit, though we saw the spots from whence they rise. After having admired all there was to be seen, and bathed our-selves in a basin about 50 feet square, one end of which is quite hot, and the other, adjoining the river, quite cold (from the latter, a Maori who was with us caught some crayfish, and taking them to a boiling spring just above our bath, cooked and presented them to us), we returned to the Wairea by the route we had come.

Thursday, 28th. — A. S. and I walked to Rotokakahi, and ascended a very high hill, from the top of which we got a magnificent view of the numerous lakes about here; we could see six at one time. Mount Edgecumbe (Putawheke) bore N. 55° E. Washing clothes, &c., rest of the day.

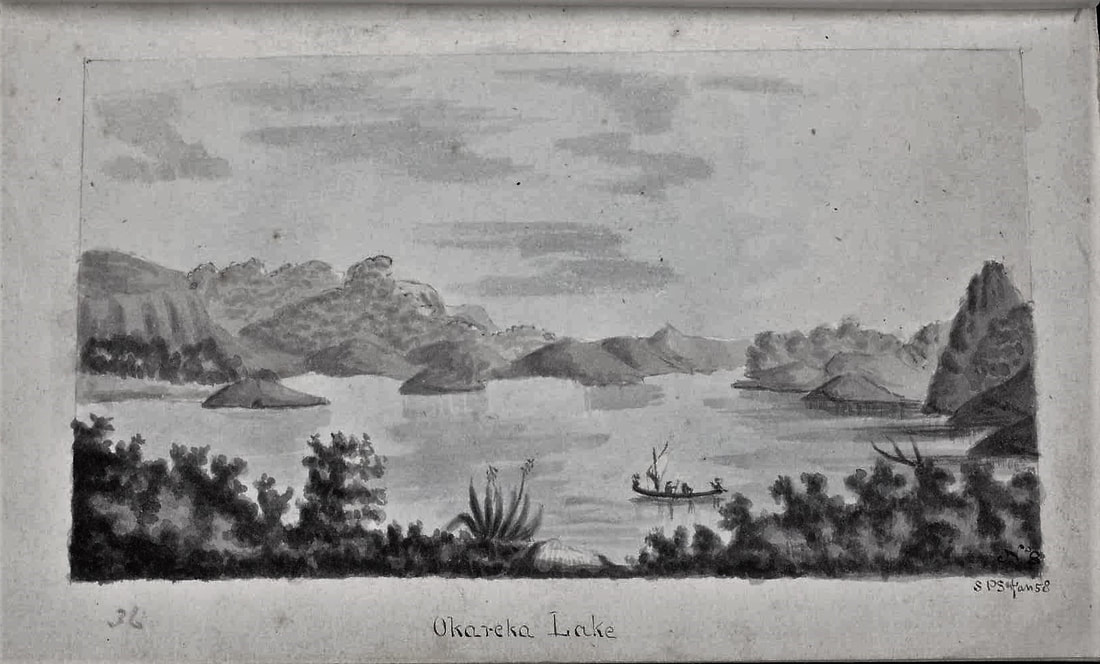

Friday, 29th. — A. S. and myself started for Okareka lake. The road leads through grassy valleys and wheat patches over a hill, from the top of which is a very fine view of Tarawera. After a little time we came to the edge of the lake, along which we continued to a beautiful small bay and waterfall called Waitangi; here A. S. took a dip in the water, and we washed off the purple stains on our faces from the quantity of tutu berries we had sucked coming along. Leaving Lake Tarawera, we proceeded about half a mile to the west, till we came out at the pretty little lake of Okareka. It is nearly surrounded by trees, and a few white points jutting out add greatly to its beauty. We observed two or three pas on its banks. It is joined to Tarawera by the Waitangi, the western half of its course being underground. We returned to Wairoa to dinner.

We then ascended a rocky path, and on the top, to our great surprise, came upon a broad cart-road, with trenches cut on each side, &c.; but we were more surprised, a little further on, when, upon turning a corner, we beheld a regular village laid out in European style, instead of being huddled up together in a heap, as most Maories live. We were met by a number of Maories, who shook hands all round, and guided us to the chief's house, which seems to be used by travellers. The chief's name is Kemp, and he seemed to be a nice, straight-forward, honest man, dressed entirely in English costume.

There was an Englishman named H. Sampson located here to impart instruction to the natives. J. M. had a letter to Mr. Spencer, which he went to deliver: and was kindly invited to stop at the mission house till we left Tarawera, which we expected to do in a day or two. The Maories have a mill here, and we bought from them 40 lbs. of flour at 2 dollars per pound. The Wairoa river (from which the village takes its name) runs just behind the house.

Tuesday, 26th. — Mr. Spencer and J. M. came down to ask us to go to Rotokakahi, which is about a mile from the mission house. We kept along the road past the mill; which is a very nice, strongly-built little place; the stone-work was done by the Maories, and speaks volumes for their mechanical skill; and passed over a little trellis-worked bridge thrown across the Wairoa river; it was made entirely by the Maories as a surprise for Mr. Spencer when he returned from a journey once; it is about 20 feet long and 5 broad, and is painted green.

We now earns in sight of Rotokakahi (lake of shell-fish; there is not one to be found in it), upon the banks of which we procured two canoes, and raced for three miles as far as Motutawa, an island situated at the western end of the lake. On it is built a pa with a great many carvings about it. Having visited the church, which is built of grass, and looks very neat and comfortable, we again started, pulled across to a pa on the southern side called Kaitiriria (all its inhabitants Catholics), and then round by the north side of the lake to the eastern end, where we got out, walked over a hill about a furlong in length, and were rewarded for our pains by a sight of the beautiful lake Tikitapu.

It is about a mile long by the same in width; in some places the trees grow down to the edge of it, and in others it is fern and manuka; altogether, it is a beautiful little lake. The water is a very deep indigo colour, and very clear; far different from Rotokakahi, the water of which is quite yellow, and full of small particles of pollen from the fern grown, on its banks. After admiring the lake for some time, we returned to the canoes, pulled hack across the lake again, and left the canoes where we found them in the morning. We then returned to the village, and were invited to dine with Mr. Spencer. He has a beautiful house and garden here, and in the latter we observed some elms and oak quite 20 feet high. The oak was covered with acorns.

Wednesday, 27th. — One of our party was now laid up with a bad leg, so as we should not be able to get to Pukawa in the eight days, the two Maories whom we left there would be off home. Mr. S., J. M., A. S., and myself therefore started for Rotorua lake. Passing Rotokakahi, Tikitapu, and a piece of bush, we entered some fine grassy valleys, along which we continued until we came to two paths; Mr. S. took the one leading to Te Ngae, the, old mission, whilst we proceeded along one that led south-west for about a mile, then sharp to the north, over some small hills, from the top of which we beheld Rotorua, the largest lake except Taupo in New Zealand. I believe it is about 12 miles long by 8 broad. It has the large island of Mokoia near the middle, which was once the stronghold of all the Maories about here, and was considered impregnable till the great Hongi, having hauled canoes overland from the Bay of Plenty, took it and massacred most of its inhabitants. It is now a celebrated place for kuineras.

We descended, and, walking cautiously among the hot springs, arrived at a settlement called Wakarewarewa, and partook of some potatoes cooked in one of the boiling springs, without any disagreeable taste, as we expected them to have. The springs about here are not near so fine as those of Rotomahana, though I believe some-times there are some splendid jets of water shooting up to the height of 30 feet; they were not at work during our visit, though we saw the spots from whence they rise. After having admired all there was to be seen, and bathed our-selves in a basin about 50 feet square, one end of which is quite hot, and the other, adjoining the river, quite cold (from the latter, a Maori who was with us caught some crayfish, and taking them to a boiling spring just above our bath, cooked and presented them to us), we returned to the Wairea by the route we had come.

Thursday, 28th. — A. S. and I walked to Rotokakahi, and ascended a very high hill, from the top of which we got a magnificent view of the numerous lakes about here; we could see six at one time. Mount Edgecumbe (Putawheke) bore N. 55° E. Washing clothes, &c., rest of the day.

Friday, 29th. — A. S. and myself started for Okareka lake. The road leads through grassy valleys and wheat patches over a hill, from the top of which is a very fine view of Tarawera. After a little time we came to the edge of the lake, along which we continued to a beautiful small bay and waterfall called Waitangi; here A. S. took a dip in the water, and we washed off the purple stains on our faces from the quantity of tutu berries we had sucked coming along. Leaving Lake Tarawera, we proceeded about half a mile to the west, till we came out at the pretty little lake of Okareka. It is nearly surrounded by trees, and a few white points jutting out add greatly to its beauty. We observed two or three pas on its banks. It is joined to Tarawera by the Waitangi, the western half of its course being underground. We returned to Wairoa to dinner.

January 1858: Lake Okareka from the Waitangi Stream

Saturday, 30th. — A. S., W. II., and J. M. went to see Okataina lake, situated about a mile from the northern end of Tarawera. They described it as one of the prettiest lakes about here, and something in the shape of a starfish, with many bold headlands jutting out, and deep wooded inlets; they also observed a settlement, but did not visit it. The inhabitants of Okataina are called bushmen by their more civilised brethren of Wairoa, on account of the few white people who visit them. C. Spencer and I went down to the lake, and we pulled about sonic time in the pretty arm at the mouth of the Wairoa river. He pointed out to me the place where the Taraweraians had sunk two large war canoes at the time of Hongi's invasion, and which they have not since been able to recover. This arm, at a particular place, is about 90 or 100 yards wide, and on one side are to be seen the roots of a large totara tree, and on the other its branches, where it had fallen across.

Sunday, 31st. — Our patient was getting much better, and we hoped soon to be on the road again. Kemp was dressed out very fine this morning in English costume, as he is preacher as well as chief. In the evening the Maories told us of a nearer way to Mokau ; one and a half days from the north end of Taupo to Rangiaohia ; one day to Pukitui ; and thence another day to Punihangarua, on the Mokau, near Motukaramu.

February 1st, 1858. — We had now been a month from home, and our friends must have expected us, as we were to have been back by this time; but there is no use in depending on New Zealand travelling, for you never arrive at your destination at the time you expect. Mr. Spencer asked F. M. to go and stay with him until he was well enough to start; so we dressed him and walked him off up to the house. The view from the mission station across the lake is very beautiful; nearly the whole extent can be seen. Tarawera is something in the shape of a cross, the largest part of which, running nearly east and west, is eight miles long; the southern part (along which we came on our arrival) is about two miles long, and is divided into two branches; the northern arm is also about two miles long. The waters of Tarawera are carried of by the Tarawera river, running from the eastern end into the sea near Meketu, in the Bay of Plenty.

Tuesday, 2nd. — Visited a waterfall on the Wairoa, down which a child fell, and was of course killed, the height being about 50 feet. It is rather a pretty fall, surrounded by trees.

Wednesday, 3rd. — F. M. and J. M. came down to help us to make damper for our home-ward journey ; we made 20 large ones about a foot in diameter, and baked them in the ashes. The Maories wanted us to go back by way of Paeroa and the Waikato ; but that would have entailed the necessity of hiring another guide, which the state of our funds would not admit of.

Thursday, 4th. — Having packed up our things, we bid good by to the Maories and Sampson, who had been very kind to us, and then went up to the Mission House to bid good bye to the Spencers. Mr. S. accompanied us part of the way down to the water. I am sure we must all bear witness to the excessive kindness of Mr. Spencer and his family, but for whom, what was to us a very happy week would have been a most wearisome one. At Poniromia we found the old man and canoe, procured for us through Mr. Spencer's kindness and forethought.

Sunday, 31st. — Our patient was getting much better, and we hoped soon to be on the road again. Kemp was dressed out very fine this morning in English costume, as he is preacher as well as chief. In the evening the Maories told us of a nearer way to Mokau ; one and a half days from the north end of Taupo to Rangiaohia ; one day to Pukitui ; and thence another day to Punihangarua, on the Mokau, near Motukaramu.

February 1st, 1858. — We had now been a month from home, and our friends must have expected us, as we were to have been back by this time; but there is no use in depending on New Zealand travelling, for you never arrive at your destination at the time you expect. Mr. Spencer asked F. M. to go and stay with him until he was well enough to start; so we dressed him and walked him off up to the house. The view from the mission station across the lake is very beautiful; nearly the whole extent can be seen. Tarawera is something in the shape of a cross, the largest part of which, running nearly east and west, is eight miles long; the southern part (along which we came on our arrival) is about two miles long, and is divided into two branches; the northern arm is also about two miles long. The waters of Tarawera are carried of by the Tarawera river, running from the eastern end into the sea near Meketu, in the Bay of Plenty.

Tuesday, 2nd. — Visited a waterfall on the Wairoa, down which a child fell, and was of course killed, the height being about 50 feet. It is rather a pretty fall, surrounded by trees.

Wednesday, 3rd. — F. M. and J. M. came down to help us to make damper for our home-ward journey ; we made 20 large ones about a foot in diameter, and baked them in the ashes. The Maories wanted us to go back by way of Paeroa and the Waikato ; but that would have entailed the necessity of hiring another guide, which the state of our funds would not admit of.

Thursday, 4th. — Having packed up our things, we bid good by to the Maories and Sampson, who had been very kind to us, and then went up to the Mission House to bid good bye to the Spencers. Mr. S. accompanied us part of the way down to the water. I am sure we must all bear witness to the excessive kindness of Mr. Spencer and his family, but for whom, what was to us a very happy week would have been a most wearisome one. At Poniromia we found the old man and canoe, procured for us through Mr. Spencer's kindness and forethought.

THE GOVERNOR'S JOURNEY OVERLAND – Daily Southern Cross 1st May 1872

Kaiteriria is a small pa on the picturesque Lake Rotokakahi, and is one of the posts held by a detachment of native militia, commanded here by Captain Mair. The Arawas composing the force are fine young men, well drilled according to English discipline, who have done good service in the war against their rebel countrymen. Kaireriria is a convenient head-quarters from which to visit Rotomahana (the hot lake par excellence) and other part of the wondrous lakes district, of which no description will be attempted here.

TRIP TO THE HOT SPRINGS – Grey River Argus 21st February 1879

At the north-east end of the lake the road branches off to Okareka where cherry, nectarine, peaches and plum trees are in plenty in the old Maori mission gardens. Between Ohinemutu and Wairoa several places can be found in the scrub where fruit trees in a wild and uncared for state abound. These have sprung up through the Maoris planting the pips of cherries, plums, or nectarines, and they now flourish luxuriantly. Tikitapu we adjudged to be one mile in length by three quarters in width. Within 20 yards after passing this lake we come upon Lake Rotokakahi or the yellow lake.

Although so near each other these two lakes are as separate as if they had been miles apart. No inter communication exists, although the former is 78 feet higher than the latter. Another proof of the wonders of this wonderful country. Rotokakahi is of a much warmer temperature than Tikitapu, and fish and pi pi's are also found in it. At its end is the island of Matutawu, and this formed the frontier post and principal camp of the defence force when pursuing Te Kooti. It is the key of the position in a military point of view to the adjoining Uriwera country. The island is about four miles long by half a-mile broad, and along its banks runs the old road to Rotomahana, now almost disused except by natives and determined pedestrians, as the easier and speedier route by Lake Tarawera has virtually superseded it. Too outlet of Rotokakahi is Lake Tarawera, and as the former is about 300 feet higher than the latter and only a little over 1 mile in distant, the , discharge rushes tumbling over falls and rocks in mad haste and furore. There are said to be splendid falls between the two lakes, but as I did not hear of them till long afterwards, I consequently did not visit them. This was about the only neglect I could lay on Henshaw in his capacity to guide. Soon after leaving Rotokakahi we came upon the Maori village of Wairoa, where there are two hotels kept by Europeans, namely, the Rotomahana by Mr and Mrs Verrall, and the Terrace by Mr and Mrs Wilson.

Although so near each other these two lakes are as separate as if they had been miles apart. No inter communication exists, although the former is 78 feet higher than the latter. Another proof of the wonders of this wonderful country. Rotokakahi is of a much warmer temperature than Tikitapu, and fish and pi pi's are also found in it. At its end is the island of Matutawu, and this formed the frontier post and principal camp of the defence force when pursuing Te Kooti. It is the key of the position in a military point of view to the adjoining Uriwera country. The island is about four miles long by half a-mile broad, and along its banks runs the old road to Rotomahana, now almost disused except by natives and determined pedestrians, as the easier and speedier route by Lake Tarawera has virtually superseded it. Too outlet of Rotokakahi is Lake Tarawera, and as the former is about 300 feet higher than the latter and only a little over 1 mile in distant, the , discharge rushes tumbling over falls and rocks in mad haste and furore. There are said to be splendid falls between the two lakes, but as I did not hear of them till long afterwards, I consequently did not visit them. This was about the only neglect I could lay on Henshaw in his capacity to guide. Soon after leaving Rotokakahi we came upon the Maori village of Wairoa, where there are two hotels kept by Europeans, namely, the Rotomahana by Mr and Mrs Verrall, and the Terrace by Mr and Mrs Wilson.

Dunedin to the North – Otago Daily Times 8th December 1877

Wairoa - From Wairoa the walk of ten miles to Ohinemutu, with two lakes to inspect by the way, was rather attractive than otherwise, on I started on a breezy morning, and at three quarters of a mile came to the lake Rotokakahi. In shape it is nearly a true parallelogram, and is surrounded by bold barren rocky hills, and in the centre of it is the island Matutawa covered with groves of keratin, and peed, apple, and cherry, and plum frees, and lots of raspberry canes and huge flax bushes. This island was the scene of a sanguinary battle that occurred some 40 years ago, between hostile tribes. One hundred men were killed. The lake from south-south-west to north-north-east is about four miles long with, about half-a-mile average breadth.

Tikitapu - Separated from Rotokakahi by a narrow high ridge, is the Tikitapu, otherwise termed the Blue Lake. It is one of the more beautiful of the many which constitute the Lake system, and is appropriately named, for the water is of a peculiar deeply tinted blue approaching the ultramarine, and no matter how the weather may be, whether clear or cloudy, this remarkable blueness is always apparent. The lake, nearly a square, is prettily set in timbered ranges, its shores bold and rocky in places. The high road between Wairoa and Ohinemutu runs closely by both the above lakes. It is made through pumice country, so exceedingly friable that the wind blows down the sides of the cuttings in tons. In one place the road is blocked up half-way across. Just sufficient room for a ‘dray’ to pass is left between the debris and the edge.

From Tikitapu, the road passes through half a mile of pretty forest, and thence across interesting open fern country until the range overlooking Rotorua Like is topped. There a lovely landscape picture is visible on the left hand, through an opening between two bald hills that is termed the Waipa Valley. Beyond this valley, the country, covered with a sea of low hillocks, opens out right and left, and the entire background of this grand panorama is faded with the dark towering Horohoro Mountain. At four miles further Ohinemutu was reached, and so terminated a five days' tour, during which I boated, walked, canoed, and rode some 100 miles.

Tikitapu - Separated from Rotokakahi by a narrow high ridge, is the Tikitapu, otherwise termed the Blue Lake. It is one of the more beautiful of the many which constitute the Lake system, and is appropriately named, for the water is of a peculiar deeply tinted blue approaching the ultramarine, and no matter how the weather may be, whether clear or cloudy, this remarkable blueness is always apparent. The lake, nearly a square, is prettily set in timbered ranges, its shores bold and rocky in places. The high road between Wairoa and Ohinemutu runs closely by both the above lakes. It is made through pumice country, so exceedingly friable that the wind blows down the sides of the cuttings in tons. In one place the road is blocked up half-way across. Just sufficient room for a ‘dray’ to pass is left between the debris and the edge.

From Tikitapu, the road passes through half a mile of pretty forest, and thence across interesting open fern country until the range overlooking Rotorua Like is topped. There a lovely landscape picture is visible on the left hand, through an opening between two bald hills that is termed the Waipa Valley. Beyond this valley, the country, covered with a sea of low hillocks, opens out right and left, and the entire background of this grand panorama is faded with the dark towering Horohoro Mountain. At four miles further Ohinemutu was reached, and so terminated a five days' tour, during which I boated, walked, canoed, and rode some 100 miles.

Tarawera Eruption - 10th June 1886

Violent and unexpected, the volcanic eruption of Mount Tarawera during the early hours of June 10, 1886, was New Zealand’s greatest natural disaster. For more than four terrifying hours, rocks, ash and mud bombarded the peaceful village of Te Wairoa. As well as ending more than 150 lives and many livelihoods, the eruption destroyed the eighth wonder of the world – the magnificent Pink and White Terraces , and buried the staging post for travellers to the Terraces – Te Wairoa village under two metres of thick volcanic material. In the gloom of the day the wreckage of the hotels and houses, and the burial of 8,000 square kilometres of scenic countryside brought awe and dismay to survivors and rescuers.

REPORTS BY OUR SPECIALS - Otago Daily Time 16th June 1886

I left Rotorua for Wairoa at 10 o'clock this morning in company with Mr Mackie, Constable Cavanagh, Mr Moss, and others in a trap. Owing to the heavy state of the road through traffic, the volcanic mud had been turned into slush, causing the trap to take two to three hours to get over the distance. It was as much as the empty trap could do to get through Tikitapu bush, the passengers walking knee-deep, in mud. The country on both sides of the road is covered two feet deep, as shown by the stones on the side of the hill. Here and there were landslips al the side of the road. On reaching Tikitapu Lake we met a group of Maori women.by the roadside who looked very dejected. The sawyer’s huts were knocked about; the force with which the mud had been driven against the front of the buildings had made it seem like cement. Along the road front doors were blocked, up by Ate falling masses, and the smashed window frames showed how the occupants had got out if their living tombs and escaped to Rotorua. On reaching Lake Rotokakahi it was found that it was again rising, though yet about seven feet below the true level, thus leaving the Wairoa river bed dry and choked with sand. It is impossible to describe.

The Desolation of Tikitapu Bush.

The storm had swept up the valley, tearing up trees, six feet in growth, by the roots, snapping off giant limbs as if twigs, and leaving a tract of forest-covered ranges as if a tornado or cyclone had swept over them. I passed through the lower valley only two or three mouths previously on a visit to the Lakes, and I could appreciate the contrast. The awful picture of desolation which met my gaze on reaching Wairoa Bridge, I hope never to witness again. It seems as if it were another Sodom and Gomorrah. Along the road were portions of personal effects thrown away in flight, overhead starved birds were flying helplessly looking for shelter, while an aged Maori sat by the roadside too weak to go on over the rough track for food. Some biscuits were given to him by the party. It. was found necessary even to bring out water to Wairoa, as the well had been filled up.

Wairoa - I failed to recall the features of the settlement. The fall of volcanic mud covered all the branches of the tall trees. On the banks of the river were to be seen, in some places; portions of fences, but in most cases all were levelled to the ground. The mill was rent asunder, and only the top of it was visible. Snow's Temperance Hall was obliterated, and the site of it could not be determined. Next to the Runanga Hut and that of Sophie (the guide) the Terrace Hotel had stood it out best, but the rear of it was all smashed in. M.Rae's was perfect wreck, while on the hill across the road could be seen the old mission church levelled with the ground. Captain Way's house was almost in ruins; while, to add to the horror of the-situation, the debris of the residence of the ill-fated Haszard family was still burning as well as the bank of sand would permit of it. In various parts of the settlement the ruins of the Native huts were also smouldering, either having taken fire when the fell at first by lightning, or by the volcanic red-hot cinders.

The Desolation of Tikitapu Bush.

The storm had swept up the valley, tearing up trees, six feet in growth, by the roots, snapping off giant limbs as if twigs, and leaving a tract of forest-covered ranges as if a tornado or cyclone had swept over them. I passed through the lower valley only two or three mouths previously on a visit to the Lakes, and I could appreciate the contrast. The awful picture of desolation which met my gaze on reaching Wairoa Bridge, I hope never to witness again. It seems as if it were another Sodom and Gomorrah. Along the road were portions of personal effects thrown away in flight, overhead starved birds were flying helplessly looking for shelter, while an aged Maori sat by the roadside too weak to go on over the rough track for food. Some biscuits were given to him by the party. It. was found necessary even to bring out water to Wairoa, as the well had been filled up.

Wairoa - I failed to recall the features of the settlement. The fall of volcanic mud covered all the branches of the tall trees. On the banks of the river were to be seen, in some places; portions of fences, but in most cases all were levelled to the ground. The mill was rent asunder, and only the top of it was visible. Snow's Temperance Hall was obliterated, and the site of it could not be determined. Next to the Runanga Hut and that of Sophie (the guide) the Terrace Hotel had stood it out best, but the rear of it was all smashed in. M.Rae's was perfect wreck, while on the hill across the road could be seen the old mission church levelled with the ground. Captain Way's house was almost in ruins; while, to add to the horror of the-situation, the debris of the residence of the ill-fated Haszard family was still burning as well as the bank of sand would permit of it. In various parts of the settlement the ruins of the Native huts were also smouldering, either having taken fire when the fell at first by lightning, or by the volcanic red-hot cinders.

The Tarawera Eruption - The Press 7th July 1909

Recently (says the Hot Lakes Chronicle) some Maoris examined a hill near Lake Okareka, where it was known a number of Maori people were living on the night of the Tarawera eruption. Now over 23 years ago, with the object of ascertaining how many perished there during that awful catastrophe. After searching for some time they found, at a depth of 5ft below the surface, the remains of 18 human being, and from the position in which some of the skeleton were found it was very evident that the parents in their love for their children made every effort to protect them from the terrible doom that was to be there. In the embrace of one adult were the skeletons of two children, whom heads had been crushed in by some falling object. Strange to say none of the skulls of the adults showed any sign of having been injured, and it is surmised that their death must have been slow and painful, and that they were hemmed in their whare by the scoria that fell during the eruption, and as it gradually increased in height all hope of escape was abandoned. The roof of the whare appeared intact, indicating that it had withstood the great weight that it had been called Shoe to bear. Among the remains were found a greenstone tiki and two greenstone ornaments, usually worn by gentlemen on their watch chains. The remains were not removed, but were rearranged and carefully covered up again.

NEWS OF THE DAY - Evening Post 29th July 1933

Taumaihi – A Maori place name carrying a military and historical significance is Taumaihi, which (writes “Tohunga” in the “New Zealand Railways Magazine”) means a sentry-tower, such as were built in the war-stockades of old. The wooded peninsula which runs out and into that pretty lake of bush, Okareka between Rotorua and Tarawera, was called Taumaihi. The name applied particularly to the rounded knoll in which the peninsula terminates; in former days in was inhabited; a palisaded village stood there. A Pakeha old-timer of my acquaintance, the late Major Benjamin Harris, gave the name Taumaihi to his home in Epsom, Auckland many years ago. He did not know of the old pa at Okareka, but he drew the name from his Maori knowledge.